Linear Barriers to Commerce and Nature

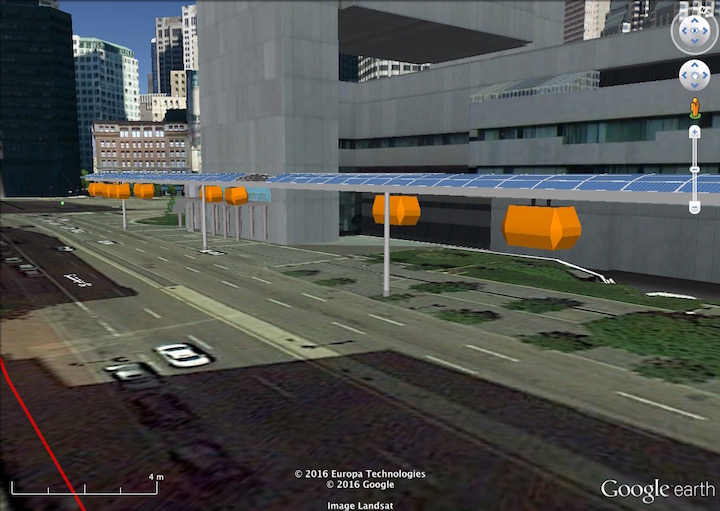

By elevating JPods networks above traffic the issue of linear barriers to commerce and social activities is preempted.

Regardless of business size, the construction of highways creates barriers to commerce. Generally these linear barriers have been built through low income neighborhoods where the abiliity to influence political decisions was low.

Robert Bullard, How Race Shaped America’s Roadways And Cities

“Transportation has always been embedded in civil rights and racism,”

REF: Top infrastructure official explains how America used highways to destroy black neighborhoods

It’s time for America to reckon with the role that highway projects too often play in ripping apart underprivileged communities around the country, Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx said Wednesday at the Center for American Progress.

In the first 20 years of the federal interstate system alone, Foxx said, highway construction displaced 475,000 families and over a million Americans. Most of them were low-income people of color in urban cores.

Setting aside considerations of intent, there is little doubt among scholars who have studied American transportation history and policy that the Interstate Highway System took a particularly cruel toll on minority communities in urban spaces. As Raymond Mohl (2004) writes, “Trapped in inner-city ghettos, African Americans especially felt targeted by highways that destroyed their homes, split their communities, and forced their removal to emerging second ghettos” (p. 700).

Indeed, black communities found themselves in the path of seemingly relentless bulldozers at an inordinate rate, a trend that became more difficult to combat given the scant political leverage among minority communities in many cities (Biles, 2014; Mohl, 2004). In Miami, for instance, highway construction captured 40 square blocks of city space, demolishing some 10,000 homes and a predominantly black business community (Mohl, 2008). The impact in Detroit was similar, as the route of the highway tore through minority communities and left behind large swatches of cleared neighborhoods (Biles, 2014).

Boston Globe, 2017: That was no typo: The median net worth of black Bostonians really is $8. The article goes on to note that the average net worth for white families in Boston is $247,500. The primary driver of this racist outcome is a century of Massachusetts and Federal transportation construction through low-income neighborhoods that repeatedly destroyed businesses, built linear barriers to commerce, and moved jobs to the suburbs for the outsized benefit of the politically powerful at the expense of the politically weak.